When we think of the long legacy of graffiti in this country most people think of New York City, and the large murals painted on the sides of it’s vast subway system. Other writers from the '60’s and '70’s like to point to Philadelphia, the home of Cornbread, arguably the first big name writer in the movement. Rarely do people look out west to Los Angeles and lump in the Cholo writing movement with it’s east coast counterparts, and yet it’s quite probable that the Cholo writing movement preceded New York, and Philadelphia.

All three movements were propelled forward in the mid-1960s with the invention of the Magic Marker and the mainstreaming of spraypaint, but Cholo writing had already developed it’s unique look by that time.

While there was always writing in the cities, with roller paint, chalk, or shoe shine polish; it was generally an individual act of vandalism - random names tagged by random people.

By the 1940s in Los Angeles, the look of the Cholo writing began to emerge. World War Two played a role, sailors on leave, bored and drunk, would chase Latinos and beat them up, the Latinos responded by forming gangs in their neighborhoods. This was the time of the Zoot Suit movement, where gangs dressed in a very unique way with long pleated pants that went up to their chests, bow ties, and wide rimmed fedoras. The look was everything. As the gangs emerged on the streets, their names emerged on the walls, in a very unique way.

Chaz Bojorquez, the leading figure to emerge from the Cholo writing movement had this to say about it’s roots. “Our west coast tradition of letter writing has a history since the 1940's. In Mexico all of the information cards for public transportation, like fares for buses and businesses, were all hand painted by master calligraphers. They were all painted in the prestigious letterface of Old English. Our west coast style of gang graffiti called Cholo is like a sign post, the graffiti states 'Outsiders Keep Out'. We would write 'Placas' (wall tags, bombs) in an advertising format similar to a billboard or newspaper with a headline, body copy and credits = gang name, rollcall of members and tag of street name or writer. In the 40's all tagging was done with a brush that wrote like a giant felt marker, still writing in an Old English style and always in capital letters and only using black paint. Around the 1950's street writing was really getting started with the introduction of the spraycan and the writers adapted the single spray line to outline the letterface creating what we call 'Block Letters’, 8-10 feet tall but still in an Old English style. I personally like and use a large chiseled brush to give me a thick and thin line, just like a giant felt marker."

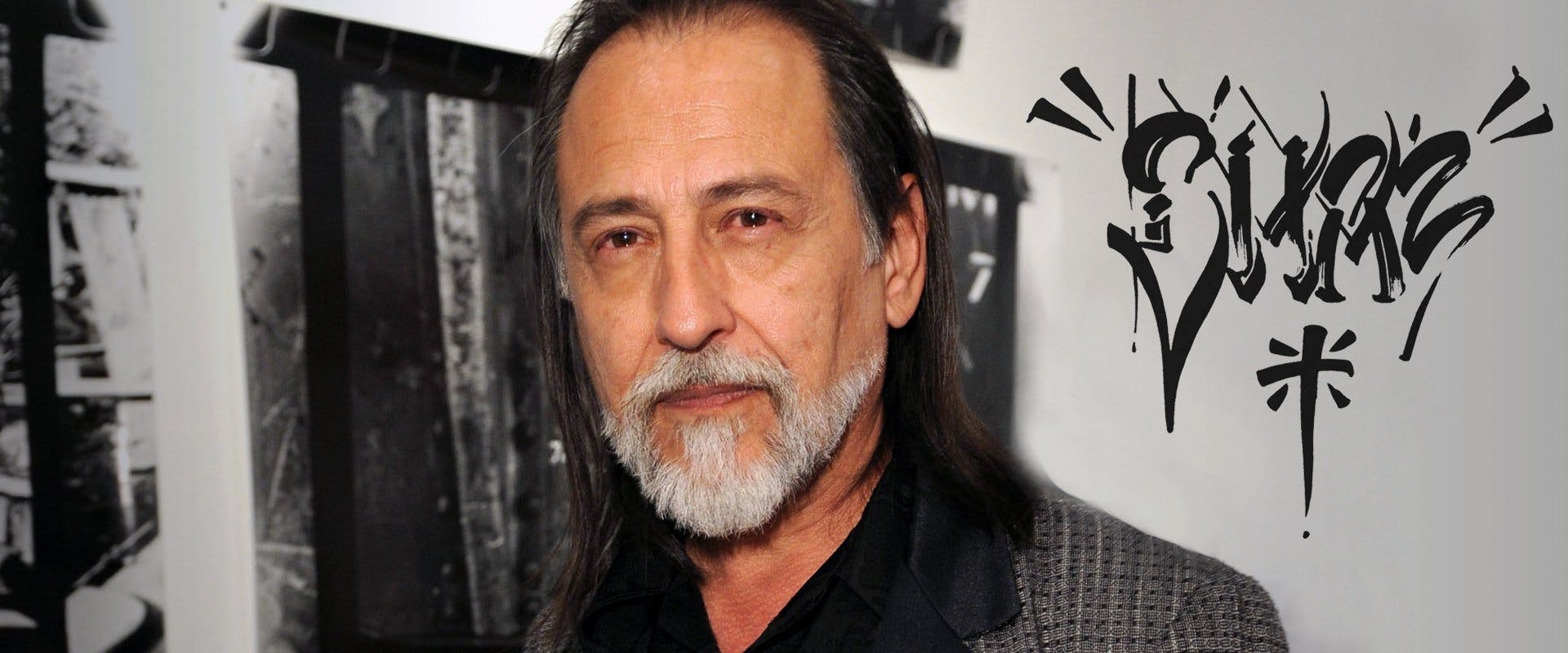

Photo by Tibrina Hobson/WireImage

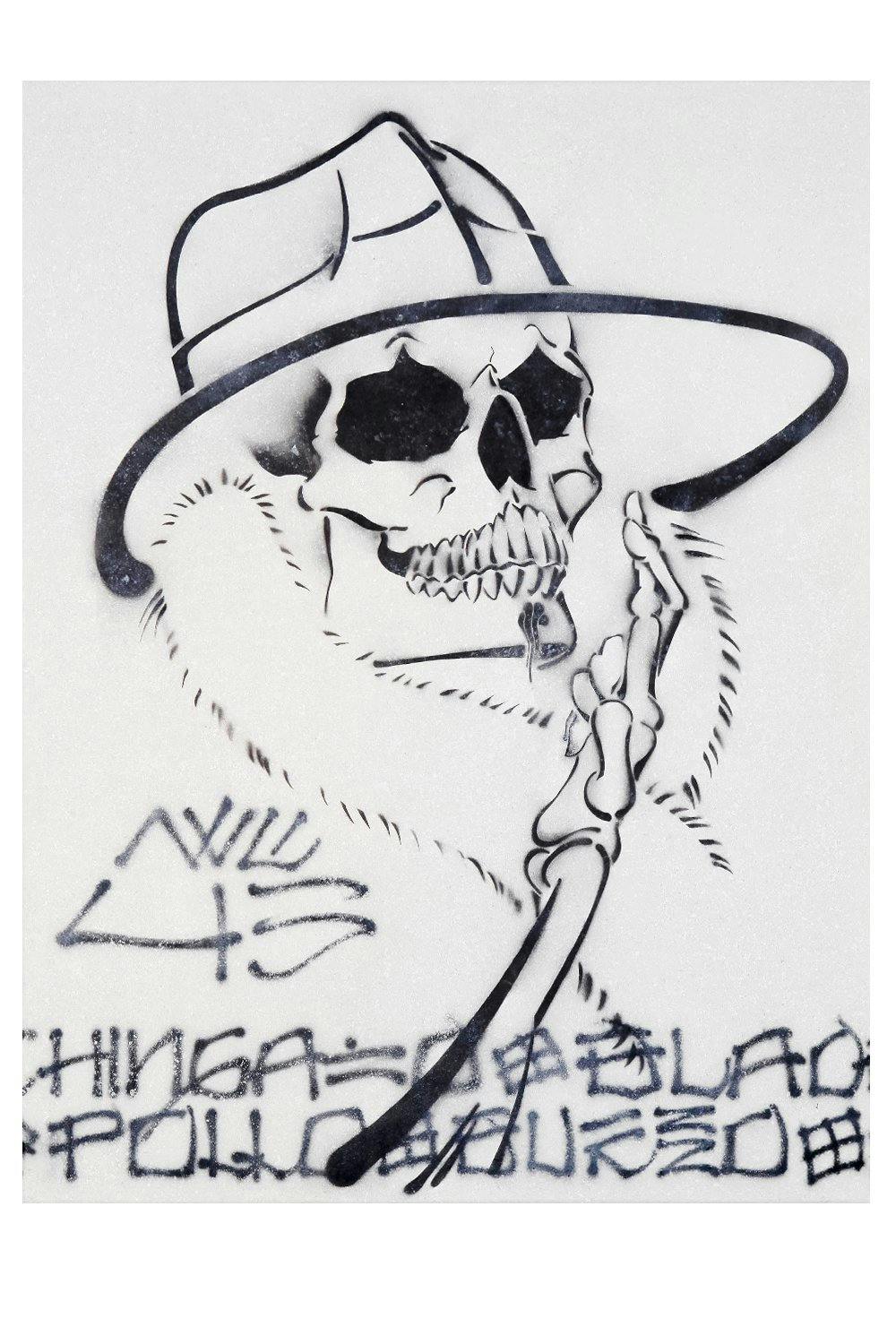

Chaz began tagging the neighborhood he lived in, Highland Park, LA, in the late 60’s. At this point, Cholo graffiti had already become a malleable art form, with letters veering away from the Old English font, Chaz began adding his own graphic vision to the streets around him. The artist began using a stenciled painting that he titled Senor Suerte ( Mr. Lucky ). The character featured a large skull with a wide grin, his bony fingers crossed for good luck. He has described it this way. “ My tag Senor Suerte (Mr. Lucky) was a composite of fashion style, cultural identity and a love for Hollywood movies. The Skull came from my Mexican heritage for 'The Day of the Dead’ and the smile from horror movies from the 1950's. I took the 1960's fashion of the New York Pimp Daddy' from the movies SHAFT and SUPERFLY. All decked out in a big Fedora hat, long trench coat plus bell bottoms and thick platform shoes. All Funk and cool.”

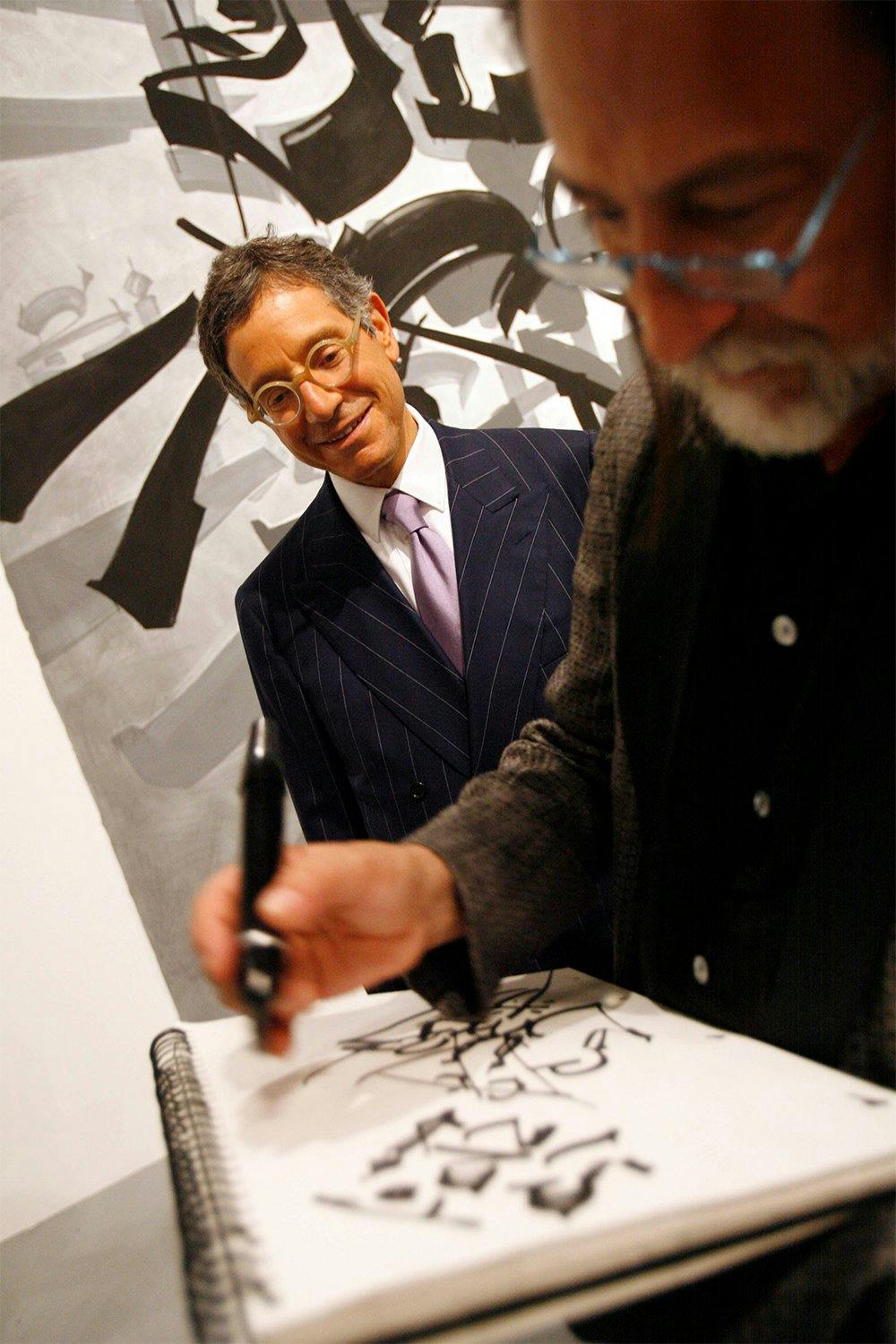

Chaz’s work could be seen in the tunnels of the LA river that criss-crossed LA, as well as the highway overpasses, and random walls along the way. Senor Suerte resonated with the other writers, as well as portions of the general public. His tagging seemed crisper, and featured enhancements such as drop shadows, an idea he took from underground artist Rick Griffin, who was inspired by the writing around him. It also helped that Chaz had taken lessons in calligraphy, and attended art school at the Chouinard Art Institute. Chaz explains how Senor Suerte would become a talisman to ward off bad luck.

“It was around the mid 80's when I had a knock on the door with two Cholo gangmembers from the AVENUES street gang. I grew up with gangsters in my school, neighborhood and some family members, so I have no fear but respect. They showed me their Senor Suerte tattoos on the top of their heads, full backs and stomachs also on their legs. It became a myth: "If you have the tattoo of Senor Suerte on your body, when you get shot by a gun, it will protect you from death" When someone believes in your art, that's the 'real' value of your work. “

In the 1980’s, Cholo writing would begin to share wall space with graffiti that had been imported from New York, which Chaz viewed as a good thing. “ When New York graffiti hit in L.A., it was a breath of fresh air, it was not about gangs, but about getting up and the image. It was 'the' major influence in Los Angeles graffiti because the young writers from the 1990's rejected the gang violence style and looked east. “

Chaz would go on to work in advertising during the day, while painting on canvas at night, until the art world paid enough for him to quit his day job.

His works have been shown world wide, and he’s in the collection of a number of museums including: The Smithsonian, LA MOCA, and the LA County Museum of Art.

*HEADER CREDIT: Chaz Bojorquez attends the MOCA Art In The Streets - Members' Opening at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA on April 16, 2011 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Craig Barritt/WireImage)